Like many other countries in Europe and elsewhere (consider the recent confrontations in North Africa), Italy has for several months been the scene of social struggles qualitatively and quantitatively unlike any seen for some time.

Already two years ago the ‘Onda Anomala’ (‘anomalous wave’) student movement involved thousands of university students against the latest case of disinvestment in the public university (the notorious funding cuts in the summer budget plan). This was combined with wider mobilization in the world of education, in which middle-school students and primary and secondary school teachers opposed the school reform of education minister Mariastella Gelmini.

Yet this failed to intersect with wider social discontent (even the ‘legalist’ left opposition to the government, embodied in the daily La Repubblica, only followed the first stages of the movement), remaining substantially isolated until it waned inexorably with the regular post-autumn decline, winning little or nothing.

With the worsening of the economic crisis, however, 2010 has seen a succession of more or less silent struggles within or for jobs and for environmental protection (l’Aquila, Terzigno1), along with various outbreaks of anti-government discontent. An important moment was the brave attempt by workers at the Pomigliano (Naples) Fiat plant to resist the blackmail of CEO Sergio Marchionne, who used the threat of moving production to Poland to restrict union rights tightly and impose even harsher working conditions. Left isolated by the other confederated unions (FIM-CISL, UILM-UIL), the FIOM (mechanical engineering section of the CGIL) and the grassroots unions won wide support and agreement in the region.

At the same time a crisis developed within the country’s governing coalition, with the final break between parliamentary speaker Gianfranco Fini and prime minister Berlusconi. As sections of the bourgeoisie in Italy (primarily large industrial capital) and elsewhere (as in the repeated attacks of the Economist) gradually abandoned their support for the prime minister, the continual scandals around his private life and the personal use of public money and structures inexorably undermined his support.

In the midst of all this the agitation around the university resumed. Contestation of an imminent reform of tertiary education started with the protest of researchers penalised in economic and contractual terms; once classes began many university students were drawn into action against a law providing for a further authoritarian shift in university management structure (including, for the first time, the possibility of direct management by appointees from the economic or political rather than the academic world) and a nebulous restructuring of the ‘right to study’, which, accompanied by reduction of the dedicated resources, effectively amounted to its abolition.

When the FIOM called a day of protest for October 16, these various perspectives found their common ground and moment of convergence. A broad spectrum of subjects not always linked to the working class condition (students, knowledge workers, movements for public ownership of water, citizen associations for legality, ‘Popolo Viola’2 etc.) came together around the engineering union in a day of high participation.

This date, one day after a national assembly at Rome’s La Sapienza university, marked the first step towards an attempt at political recomposition which was perhaps less effective than promised. From that day onwards a series of assemblies, conventions, episodes of joint protest, etc represented the difficult, contradictory, often only symbolic attempt to build a process common of struggle between the fragmented world of work and a world of education which maintained a constant state of agitation in the battle against minister Gemini’s restructuring, albeit almost exclusively in the political practice of university students.

Meanwhile, in a climate of more or less manifest political upheaval, the internal crisis in the governing coalition continued, with the government forced to schedule a new confidence vote for December 14. The social movements took the opportunity to manifest their vote of no confidence, which had no need to pass through parliamentary balancing acts, but was built from below: they called a day of street protest for the same date.

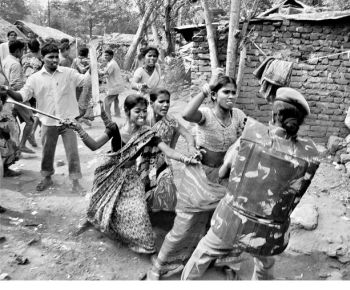

‘Inside the palazzo’ that day the buying and selling3 of MPs narrowly guaranteed the survival of the Berlusconi government, while in the street young students, workers and the unemployed wrought havoc in the city. The street actions had the broad support of the students, who had withdrawn from the game of reformist politicians who sought to distinguish ‘good’ students from ‘bad’ ones. For all its contradictions and its largely incidental nature, this was a moment of meeting and consolidation between diverse subjects in the same practice of conflict.

Partial confirmation of this came shortly afterwards when Fiat CEO Marchionne turned his blackmail on the workers of the company’s Turin Mirafiori plant (Italy’s largest industrial complex), once again threatening closure unless a new agreement was accepted including the substantial elimination of significant union rights along with harsher working conditions. Although the other confederated unions sided with management again, FIOM and the grassroots unions were not alone in their contestation. Despite a narrow defeat in the plant ‘referendum’, which nonetheless showed workers’ determination not to give in to the blackmail4, many demonstrations of support and solidarity came from a large part of the student movement – which immediately joined in the January 28 strike – and beyond.

In relation to capital, the FIOM, the union of Italian mechanical engineering workers, has been and is a counterpower and a co-manager according to varying circumstances. Its base is classically working-class, although with a new composition today, incorporating young people, migrants and women. In contrast to other European countries, new forms of worker organization are not emerging alongside historic unions. Rather, over the last few months an alliance has developed under the slogan ‘United against the crisis’ between FIOM and other grassroots subjects (certain social centres associated with the so-called disobbedienti). Currently there is an attempt to hold together the most typically welfare-oriented demands (basic income) with the historic demands of the unions (working conditions). Significantly, the January 28 marches opened with the slogan: ‘labour is a common good’.

Struggles in the worlds of work and education continue to intersect, fluctuating between, on one hand, genuine moments of confrontation and conflict undertaken collectively and, on the other, tactical alliances, manoeuvres around institutional margins and more or less symbolic encounters.

The roots of the trouble

In the last two decades the Italian economy has seen the withdrawal of big business (which now seems to be reaching its final stage with the fate of Fiat), privatization transforming public goods into easy income for rent-seekers, the crisis of industrial districts and perpetual industrial dwarfism. At the same time it has seen the emergence of thriving small and medium businesses, the so-called pocket multinationals. What has been called Italy’s ‘fourth capitalism’ has therefore combined a labour market dominated by deregulation, fragmentation across large and small companies and ever more accelerated precarization with the capacity to become Europe’s second-largest manufacturing exporter, including significant niches and sectors. Thus Italy is a link between the high-technical composition production of the north, where high-end consumer goods are produced, and the high-exploitation production of eastern Europe and Asia, where conditions of low-cost, long-duration, high-intensity labour are accompanied – in contrast to the old underdevelopment – by the ability to enter non-mature sectors and relatively advanced production.

Entire sectors of Italian technological research, such as chemicals and electronics, have been broken up, even as economic miracle of the northeast is praised: a low-investment economy which has compensated for a low technological level and almost non-existent research with long working hours stretching through Saturday and Sunday, the atomization of the production process and the elimination of unions. Where investment and technology remain, the subordination of labour is maintained and aggravated, thanks in part to the network structure of the new capitalism, which has overcome the dichotomy between large companies (where unified working conditions and contracts applied under a single roof) and small ones. This centralization without concentration of capitals was certainly made possible by innovations in transport and communications, electronics and information, but it was above all the response to a high level of conflict which still leads the capitalist class to fear large concentrations of workers.

The individualization of labour contracts and dismemberment of collective labour have reached paroxysmal levels, sometimes counterproductive for the work itself. But in this situation the youth have found their own sea to swim in, refusing as far as possible to stay trapped for life in monotonous, repetitive or low-waged work. The youth live on benefits, parents’ savings and often in their parents’ houses, with restricted consumption and informal work. Almost a third of young Italians are unemployed, but among them are many fleeing a fate of precariousness and lowered expectations. What sociologists call a ‘mismatch’ in the labour market, i.e. the presence of the unemployed and of available jobs, is increasing. Young people with high educational credentials do not find corresponding jobs. These young people, together with those who are still in education and already recognize their miserable future prospects, form the hard core of the protest.

The recovery of a collective dimension

The struggles of the last year appeared against this background of economic and social dislocation, with the institutional and political crisis of the Berlusconi government superimposed. If in recent years precarization as a psychological and ideological means of governing labour power has pitted everyone against everyone else, these struggles seem slowly to be picking up the red thread of the collective dimension. If fear and resignation continue to prevail among many workers and students, many others sucked into the crisis respond, as we have seen, with practices of openness towards other social and working subjects.

In Rome as in Athens with the attempted assault on parliament and in London with the successful assault on the Tory headquarters, this has culminated in a tough response to the violent self-referentiality of a political class which has cut off every relation to so-called ‘civil society’. If the demonstrators have been violent, this has been in order to end the violence of European governments. This latter violence, manifest today in states-of-exception-become-the-norm and continuous emergency government, cannot be contained within the limits of the legal state [Stato di diritto]5, because it constitutes and expresses the nature of the state itself. Just as the police baton charges express the ‘democratic’ nature of the maintenance of public order in the name of the people. The undisguised violence of the state today is not the result of a ‘deficit of democracy’, to be corrected by a bit of democratic participation and ‘civil society’; it is the outcome of a process begun symbolically in 1987 with Margaret Thatcher’s words: there is no such thing as society. There are individual men and women, and there are families.

That phrase was not a beginning but already an epilogue to a series of struggles and conflicts. It initiated a new round of attack on every remaining echo of the ‘common’ and ‘collective’: rights, work contracts, health, services, housing. These rights and collective contracts did not grow through some natural maturing of legal civilization: they were won by the struggles of the labour movement, which defended them as far as it could. These collective rights are an anomaly in the normal course of the modern state, which whenever it is necessary or useful to do so redefines the relation between power on one hand and the mass of individuals on the other, hollowing from the root or abolishing the supposed guarantees or presumed rights regarded as the ‘normality’ of the legal state by politicians and unions of the ‘left’, whether moderate or radical. It is not a question of putting the state machinery back on the rails of juridical normality, but of restoring the anomaly.

The deception of the ’80s and ’90s is not a matter of a political class that failed to care for its children, but of the neutralization of politics through legal rights. The so-called left wanted to democratize the state through creation of new rights to be conceded to individuals and disadvantaged minorities. As this logic gradually acquired legitimacy even among the representatives of the labour movement, collective rights were undermined and the right of the working class to exercise violence in their defence was eroded. This perspective was generalized, at least until a few months ago.

The current mobilizations have cut across this perspective, revealing the deception of political representation and bearing witness to a conflict between struggle for rights and for common goods.

Capitalism, which develops the conditions of struggle for democracy, erodes them at the same time. Capital is fundamentally incompatible with democracy: rather, its nature is totalitarian in a strict sense. Democracy comes to it from ‘outside’, from that radical alterity which it must nonetheless always ‘incorporate’: that is, from ‘living labour’, from its dependence on the struggles of workers in flesh and bone, mind and body. Rights are either founded on a power that passes through places of work, or sooner or later they simply become an empty simulacrum. But this requires the construction of a different politics and practice of democracy: of another kind of democracy. One that moves with uncertain steps, prefigurations and anticipations every day, in concrete and material struggles.

In search of a common ground

But for as long as the unifying category for the various subjects involved in this political practice is identified in the common condition of ‘precarity’ – a descriptive and psychological category which cannot give a name to the rage expressed in the episodes of collective revolt – any prospect of real collectivity [comunanza] remains substantially vulnerable.

For as long as the student revolt remains the expression of the rage of a young generation that fears being left with ‘no future’, feels ‘predestined to live marginal or precarious lives’ and comes onto the streets to ‘force the older generation to accept responsibility’, this rage, as undefined as the expression ‘precariat’ (which follows the Italian fashion for turning adjectives in to nouns), remains the rage of someone betrayed, directed against another who should have protected him or her and failed to do so. It closely resembles adolescent rage against social maternalism, which first almost drowned its children in the warm honeyed milk of a social existence totally organized and protected by benevolent institutions and friendly parents, then betrayed the expectations of the same young people who claimed as an individual right a guaranteed job matching educational qualifications. For as long as the talk is still of ‘young people’ and ‘students’ and the latter continue to represent themselves this way, they can demand a ‘basic income’, which is no more than the perpetuation of pocket money from mom and dad, but the scenario has not changed by a millimetre from Thatcher’s: there are individual men and women, and there are families.

When, as is particularly clear in the claims of the engineering and natural sciences students, this rage seems exclusively directed against a political class guilty of failing to grasp the syllogism that research investment leads to innovation and innovation to competitiveness against ‘first division’ countries – in short, against a political class guilty of managing a ragged capitalism – it’s clear that this ground, rather than constituting the basis for a ‘recomposition’ of social movements, lends itself quickly to their ‘decomposition’, given that the burden of defending the ‘young’ and the ‘students’ from precarity could be transferred to their ‘sheltered’ elders, perhaps by cutting pensions or other parts of the welfare state, or by further squeezing workers within the productive cycle. Or by positioning Italy ‘better’ within the international division of labour, asking the public system (and the private) for more investment in research and development.

Whether a ‘living income’ is claimed based on the illusion that human beings produce value generically in their every activity (or inactivity), or whether a place in the sun is claimed only for the ‘men of science’ precious for economic growth, the political result is the same: instead of struggling for historical and social subsistence as part of a class, independently of any contribution to valorization of capital or use value determined in capitalistic terms, the claim is limited to elevation of one’s own status, improvement of the conditions of one’s own category even at the cost of exploiting someone else. (There is a distinction to be made between ‘guaranteed minimum income’ [reddito minimo garantito] and ‘basic income’ [in English in the original and in many Italian texts making this demand]. But the political question is that of overcoming the redistributive plane and connecting the wage struggle to what, how and how much is produced.)

The dynamic of capitalist development in Italy and elsewhere shows how fragile this prospect can be. The so-called ‘road to competitiveness’– invoked by those who call for more research investment and exalt an over-generic ‘knowledge economy’, counterposed to ‘material’ labour – produces surplus value only thanks to the convergence of higher labour productivity, higher intensity of labour and a longer working day. This simultaneous extraction of relative and absolute surplus value is present everywhere, throughout the transnational chains of valorization. Thus the combination recurs in various geographical areas (the western metropoli, eastern and southern Europe, etc) and in various sectors of production (units of ‘low’ and ‘high’-technology capital). As the case of Marchionne demonstrates, in supposedly high-relative surplus value production the violence with which capital imposes its autocracy in the factory is increasing vertiginously, showing ever more complete indifference to the physical and mental health of workers.

The reforms of the education cycle over the last 15 years – of which the ‘Gelmini reform’ is only the latest episode in a largely continuous series – are not just a mistake of foolish political bureaucrats, but an attempt to synchronize the education mechanism with the capitalist rationalization of knowledge. The reduction of knowledge to packets of information does not require large-scale investment, because these packets are socially available thanks to cheap technology and can be taught in secondary schools and universities by teachers as ‘precarious’ as the information they transmit. These packets are commodities like any other, they can be bought and sold on the market and their production in research laboratories offshored.

However education as a system of production has another function, that of producing workers. This production is as essential as that of commodities. For one part of ‘post-fordist’ production the workers produced by the education cycle need not have particular qualities, but they must learn a particular attitude, that of ‘learning to learn’, designated by the EU as a key skill. They must ‘learn’ the packets of ‘disposable’ information administered through the education process, thereby ‘learning’ that education now functions as ‘operating instructions’ for a new procedure that will quickly become obsolete, at which point new operating instructions will be required in the course of ‘continuous education’.

Meanwhile the other aspect of production really does entail a higher level of labour participation and qualification, requiring workers’ active engagement more than ever before, given the construction of apparently idiosyncratic and non-massified use values, the flexibility of a labour cycle subject to countless alterations and shocks, and the transfer of value from means of production at risk of ever-faster obsolescence. But the partial requalification of labour and the limited autonomy of men and women in production constitute an intolerable risk. Therefore they must be controlled, no longer directly or through an overly linear dequalification, but through the appearance of market domination over production (the stock market that sets the pace for valorization of capital, the spurious restrictions of foreign trade or public finances, but also the ‘make or buy’ system, decentralization, outsourcing, in-house-outsourcing). Through the pursuit of ‘education credits’, workers learn from their student experience onwards not only to regard the content of study with the utmost indifference, but to respect and adjust to the time-imperatives and the logic of the market. Confusedly present withinthe student struggles, therefore, are both the awareness that not everyone can reach this level of education – although it is supposedly open to all – and the disappointment or rage of unmet expectations.

The process of capitalist rationalization of knowledge has changed not only educational institutions but also the nature of knowledge itself. On one hand it is broken down into packets coded according to objective mechanical function, and on the other it must provide qualifications and specializations exceeding their given sense and context. The ‘how’ must be taught without the questions of ‘why’ and ‘for whom’ ever arising. The alternative is no longer between public and private schooling; the question is not even that of common appropriation of this intrinsically capitalistic and informationalized knowledge: these are dreams, yearnings of those educated in the school of Gentile and of young people in search of easy slogans.

Thus education, knowledge and labour must be discussed starting from our own needs, in order to determine what and how much is produced and how. Whether in a factory or call centre, where knowledge incorporated into means of production serves to squeeze labour, or in the places where knowledge is produced without regard for any real quality or significance other than market value, the purpose is perpetuation of a model of development whose dedication to profit is matched by its indifference to physical, moral and environmental devastation.

Until a few years ago these ideas would have been regarded as mere ideology; their reappearance now is imposed by the objective crisis of capital and by the struggles of subjects within and against this infernal mechanism. Today the common ground can be constructed on which workers and those in university struggles, researchers and students, are able to meet, as they have already met in the struggles of recent months.

Comrades from Italy, march 2011

footnotes

[1] Terzigno: town at the foot of Vesuvius with a huge toxic waste dump and abnormally high incidence of cancers and other lethal diseases. Locals have resisted plans for a second dump with physical force.

L’Aquila (Abruzzo): survivors of the 2008 earthquake were attacked by police in July 2010 when they protested in Rome against derisory ‘reconstruction’ and ongoing homelessness. Apparently they failed to appreciate the ‘solidarity’ (Reuters) shown by the government in moving a G8 meeting to the ruined city.

[2] The Popolo Viola (purple people) movement was formed through the internet. The name emphasises non-alignment to any political party. They are against Berlusconi and deeply attached to the legal state, demandng ‘legality’ and freedom of information. Through virtual ‘social networks’ the movement brings together petit-bourgeois who think the question lies in an awakening of democratic consciousness.

[3] Palazzo: literally, not a palace but a large, usually official, building. Since its use by Pasolini in a newspaper article of 1975, the phrase ‘inside/outside the palazzo’ has taken on the wider connotation of inclusion in/exclusion from the hermetic system of official business, politics and history.

‘Buying and selling’: at least according to the ‘legalist’ opposition press, this should be understood literally rather than figuratively.

[4] In the ‘referenda’ of workers at Pomigliano and Mirafiori the percentage of votes against compliance with the Marchionne blackmail significantly exceeded combined membership of the FIOM and the grassroots unions.

[5] Stato di diritto: sometimes also translated as ‘rights state’; no exact English equivalent exists for the convergence of ‘right’ and ‘law’ in diritto. Whenever either ‘law’ or ‘rights’ [diritti] appears in this text, the other is also strongly implied.