Gautam Navlakha and Asish Gupta

After two months of persistence Bastar Sambhag Kisan Sangharsh Samiti (BSKSS) could hold its first rally cum public meeting on June 1, 2009 in Jagdalpur to protest displacement of adivasi peasants from their land and forest as well as construction of Bodh Ghat Dam, privatization of mines and river water resources. As the only two ‘outsiders’ we looked on as streams of people at the height of summer month walked raising slogans and their fist. They gathered at College Campus and then from Dharampura the rally made its way to Indira Priyadarshini Stadium. Their short but wiry bodies in terms of age and gender may have been different but the steps they took, many barefoot, were determined and firm. After the rally as people made their way into the Stadium some were seen leaving in a different direction. These were people who had arrived the night before had to travel long distances to return home and anxious to do so before dusk fell. But those who remained behind for the public meeting sat under the shade provided by canopies rented by the organizers. They sat down to listen. Slogans had been shouted now was the time to hear what their own people had to say.

Organisers claimed 20-25 thousand adivasi peasants came for the rally at Jagdalpur on June 1. There were certainly more than 15 thousand people in the rally, local scribes affirmed, maybe even more. But no one was doing a headcount so it remains a guesstimate. Numbers apart the turnout was nevertheless impressive given that the administration had given the permission just the day before, after more than two months of prevarication, on morning of Sunday 31st May. For so many to come at such short notice from four of the five districts (Narayanpur, Bastar, Dantewada, and Bijapur), which comprise Bastar division, was no mean achievement. Lohandiguda peasants walked all the way as did those who came from Abuj Madh across the river Indrawati. Others walked and then took bus to reach Jagdalpur. They came because their very existence is under threat. Many could not make it, especially those from Kanker district, which boasts of the infamous Jungle Warfare School, which trains soldiers to become more proficient at fighting their own people. According to the organizers transporters were told by people in the administration in Kanker not to provide buses. There was no way to cross check this claim but there were people from four districts.

Those who came did not come to listen to some potentate or leader from Raipur or Delhi. The BSKSS did not pay them money to entice them there. They came to lodge their protest and listen to their own who addressed the gathering in their individual capacity, keeping their party and other affiliations aside. Many had been until the other day at loggerhead. Thus entire spectrum of politics belonging to the right and left including sadhus/mendicants addressed the gathering. Some spoke in Gondi and others in Hindi. But the message was more or less the same. All voiced their opposition to government’s development policy, and were determined to fight in the common cause of saving Bastar from an administration which was backing the capitalist profiteers and marauders, not our words but this is how the speakers described them.

The supposedly ‘national’ media was of course unaware of the rally and meeting since their “sources” either did not inform them nor was this a sensational incident (euphemism for landmine blast/jail break…) to vent their outrage where Bastar is concerned. The local media of Bastar alone reported the event. And they covered it truthfully. But, the administration remained alert, which is to say fearful, till the very end with huge deployment of security forces. Jagdalpur edition of Navbharat newspaper (2 June, 2009) reported that the administration and local industrialists were taken aback by the large turnout because permission had given just the day before the rally and yet people were mobilized in such large number. They also pointedly referred to the fact that this was the first time ever that such a large rally cum meeting was organized entirely by local people. Haribhumi, another local newspaper, wrote the next day that peasants who came paid for their own travel and that the administration was caught unaware by the rather well organized event. Local edition of Dainik Bhaskar (June 2, 2009) added that throughout the rally and public meeting the officials remained busy monitoring what was happening.

Be that as it may. In their memorandum, addressed to the Governor of Chhattisgarh, the organizers list various proposed projects, including that of Tata, Jindal, Essar and Mittal for which MoUs have been signed. They point out how the Tata Steel project (for which, coincidentally, the MoU was signed a day before the formal launch of Salwa Judum in June 2005) has through ‘stealth and use of force’ got peasants to part with their land and then forged compensation paid to the peasants. They wrote that they were in possession of at least 100 such cases of forged compensation. The memorandum mentions that Bodh Ghat Dam not only ‘poses environmental threat but submergence of thousands acres of forest land’, which in turn also means loss of minor forest produce for the adivasis. They go on to refer to privatization of mines in Chargaon, Ravghat, Kuvve, Budhiari, Madh, Amdai, Metta among others, which will ‘benefit private companies not the people of Bastar’. Finally they refer to the fall in water level in parts of Bastar region due to the Essar pipeline meant to transport fragmented iron ore from Dantewada to Vishkhapatnam.(1) All this means, according to them, loss of livelihood and destitution for an already impoverished peasantry. They instead asked administration to help promote agriculture, provide power, construct ponds, check dams, small dams, lift irrigation, build anicuts, promote forest based cottage industry and small industries as an alternate model of development.

The handbill which was distributed in thousands and blown up as a poster across Jagdalpur town provided more details. To cite some portions of the handbill, in our freely translated version, it reads:

“Brothers and Sisters, come look at the lethal pro capitalist development of Bastar. In the name of development and employment Bailadilla mines were started. Iron ore is being exported to Japan, South Korea and China at a throwaway price. Railways were started in the name of public interest. There are tens of goods trains but a single passenger train. In 1978 when people were demanding permanent employment they were fired upon and tens of adivasis were killed, thousands of huts were burnt to ashes. Thousands of adivasis were rendered homeless and left to fend for themselves. Women of Bailladilla were dishonoured and sexually abused. We want an account from Bailadailla of Bastar’s purported development.

Four decades ago at a cost of Rs 250 cr Bodh Ghat Dam was proposed and Rs 50 cr was spent on the project but then suspended because of popular agitation against it.(2) We would like to record our appreciation and contribution of pro-people Dr B D Sharma.(3) So why have they revived the same project at a cost of Rs 3600 cr? How come the Ministry of Environment cleared the project? Instead of Polavaram and Bodh Ghat etc big dams why no irrigation is being promoted through ponds, small dams, check dams, lift irrigation, anicut etc? Despite the people deciding not to give their land, why is it that land belonging to 10 gram panchayats of Lohandiguda is being forcibly acquired? Why are people being threatened and warned? Why is there lathicharge? Why are more than hundred people behind bars? Why are teachers and doctors being used to help Tata acquire our land? Why is it that 300 persons in Nagarnar been sent to jail? Why is Essar company been given permission to transport iron ore through a pipeline? Why despite the presence of railways has permission been given to divert river water to Bay of Bengal? In whose interest is it when it railway earns Rs 300 per tonne whereas its costs Rs 30 per tonne through the pipeline? Is it not true that in order to benefit Essar to the tune of Rs 270 per tonne people of Bastar and land is being deprived of water? Why?”

The rally cum public meeting and the demands along with 28 slogans (distributed among the participants) gains also in significance against the war being waged in Chhattisgarh and elsewhere (Lalgarh being the most recent) by the Indian state against Maoists and it is therefore, the context is important to keep in mind. It is also a salutary reminder as to how alien Indian corporate media is, barring honourable exceptions, from ground reality and how malleable they are to Indian state’s manipulative ways.

When the organizers were queried as to why according to them the administration appeared reluctant to give them permission when the newly formed organization comprises people with diverse background from as far apart as communists to RSS. Indeed some of the officer bearers fought the recently held elections. For instance, president of BSKSS, Subhash Chandra Maurya from Usribera in Lohandiguda block fought as an independent candidate and polled 31,000 votes. He began as RSS activist and was in BJP for many years before joining Uma Bharati’s Bhartiya Jan Shakti party. So what persuaded him to traverse an entirely different path now? According to him Tata Steel project will affect at least ten villages in the Lohandiguda block, mean loss of nearly 5500 acres and deprive 9-10,000 families, which could go even up to 20,000 as they apprehend, of their livelihood. According to him their land is fertile and multi-crop land with up to three crops a year. He asserted that fake gram sabha meetings were organized by the administration to elicit consent for alienation of their land to the Tatas in Lohandiguda. He said rhetorically why do the Tatas not setup their plant in Jagdalpur instead of destroying their villages if they are so keen to bring development to Bastar. Organisers said that they had trying since late March through April and May to plead with the administration to give them permission. But the city magistrate which is authorized to give the clearance used one pretext or the other to deny them this. First they used the pretext of elections to deny permission. But once polls were over it became clear that the reason was their fear that Maoists were behind the effort.

Bonjaram Maurya, patron of BSKSS, in his speech told the gathering that administration was reluctant to issue permission because they feared that Maoists were behind their effort. He told the audience that he informed the administration that while they ‘brought his people to the roads’ (meaning Salwa Judum) Maoists supported them. He said that he told the administration that why should they reject the support extended to them by the Maoist for their demand, and if the administration is so concerned why don’t they listen to the people. He told the gathering that although 61 years have elapsed government behaves like the British colonialists towards the poor, workers and peasants. Thus it went when speaker after speaker Balram Majhi, Budhram Netam, Jai Singh Sodhi, Suresh Sargam, Budhram Poyam, Rajman Benjam, Bangaram Sodhi …spoke. Not one spoke against the Maoists, the alleged outsider and their ostensible oppressor, but all of them spoke against the government and the corporate houses for destroying them and their Bastar. I asked many present why were they silent about Maoists. They were in a ‘safe zone’ with police all around to protect them from Maoists? Did they not fear the Maoists who are supposed to have oppressed them? Subhash Mauraya spoke for many when he said that he began his political life as an RSS activist and had supported Salwa Judum. But not anymore. “It is our adivasi brothers and sisters”, he said, “who are being pitted against each other”. Does it mean that Maoists are also adivasis? Of course yes, he replied. What about Dadalog? A person who chose to remain anonymous said they speak better Gondi than many of us, thus hinting at the organic link that exists between the Maoists and the people. He then went on to say that it is not the Maoists who are grabbing our land, destroying our forests, privatizing and polluting the rivers but the corporation which are being supported and aided by the administration. So why should they fear the Maoists when they too hold the same view, he said? When I asked others if they endorsed this view they joined in to tell me that Salwa Judum has brought disaster and we don’t want these soldiers here. It was pointed out to me that there was a connected between corporate land grab and Salwa Judum, because since it began these projects began to be proposed and administration has been coming down heavily on them to remove them from their land and forests.

We asked them as to why did they not invite well known personalities from far and wide to give their organisation wider coverage. We were told that it is difficult when they were not sure if they would get permission. On two occasions when BSKSS had settled on a date they had approached three personalities but because permission was not provided they could not persuade them to participate. However, they also added that it did not matter because right now they have to consolidate their organization and it’s only when they are united and strong that inviting people from outside would be effective they said. Why so, we asked? Because they did not want their voices converted into something they do not want. We recalled that in the speeches given it was emphatically asserted that they were not interested in land for compensation. They did not want to part from their land. They said that they had approached just three or four persons who were unattached to any group and that they decided that they must first build up their own organization so that when they invite someone from outside they get the support along the lines of their demand. We told them that Adivasi Maha Sabha had organized a much larger gathering two years ago (November 2007) and that end of May this year they had organised a large meeting in Lohandiguda. But they appeared to be reluctant to say anything except to say that AMS is connected to a political party and cannot represent every one of them. Was this an implied criticism of AMS and funded social activism? I really cannot say. Nor did I probe this any further. But what it does suggest is that there appeared to have been much discussion and debate that preceded the crystallisation of views and formation of the organization into the form it has taken. Giving it a non partisan character, ensuring that all official posts are so divided that every view finds representation and that all are drawn from the affected community. The only disconcerting thing was the absence of women speakers (barring one) and women activists in leadership position whereas women were well represented in the gathering. Surely if the Maoists had been in control of the formation of BSKSS they would have ensured the presence of women. In this sense administration’s fears appeared exaggerated and verging on paranoia.

Will the BSKSS be able to sustain its struggle? After all the state is strong and cunning and has enormous resources at its command to weaken them, we asked? They said yes they were aware of this but their only strength lies in their unity. If they are able to ensure unity they will be able to force the government on the back foot. Nandigram and Singur came easy to their lips as examples of what the people can achieve.

Now if some proof was needed about the disconnect between the projected reality by the state, and force multiplied by the corporate media and the ground reality as it exists, it was available here. Here was an organization of persons directly affected by corporate driven development being foisted on them. Maoists derive their legitimacy for their actions armed and unarmed from this. And it does appear that but for the Maoist presence here these voices of protest of the oppressed would have died down a long time ago in the sea of ignorance and indifference in which the Indian state and its acolytes want the country to descend. It does not mean that Maoists are above criticism. But their critics must display intellectual honesty in admitting that the Maoists are not ‘outsiders’ or middle class romanticists of 1960 vintage but are the underclass who have been mobilized because people are no longer willing to sit by and wait for fruits of development to trickle down at some distant future.(4) Some of them still swear by politics of agitation others are convinced that the state and society must be transformed. The people do not perceive a divide between them as much as lazy intellectuals contend. Therefore, the disconnect between the Maoists and the people is as unreal as the rift between the people and the State which is carrying out a savage war for ‘development’, real. In the war in Bastar, BSKSS effort shows that their wrath is reserved for the state which for decades treated them as less than humans and is now busy promoting rapacious corporate capitalism. It is for us then to decide which side of the barricade we belong to.

Notes:

While taking the full responsibility for any inference drawn by them and their own reading of the situation, the authors wish to record their appreciation of candid views and help offered by BSKSS.

(1) Essar transports fragmented iron ore by using water and chemicals making it into liquid slurry. It is then transported through a 267 km long pipeline, completed in 2006, with a controversially broad 20 meter breadth instead of 8.4 meter breadth. The diversion of water for the pipeline is what BSKSS was referring to. Ashok Putul in “No Man’s Land” points out that Tata Steel, with which the MoU was signed on 4 June 2005, i.e. a day before formal launch of Salwa Judum on 5th June 2005, wants 25 million gallon of water daily. Essar, which signed its MoU in July 2005, first asked for the same amount and then raised it by an incredible 2.7 times. According to him 4000 ponds have dried up in Bastar.

(2) Bodh Ghat Dam was refused union environmental clearance in 1984 because rare specie of century old Sal tree forest was threatened with submergence. This year just prior to the general elections it was cleared under the argument that compensatory afforestation had been reached. The impact of dam on people and their livelihood needs was never an issue either then or now.

(3) Dr B D Sharma is one of the most respected and loved IAS officer turned activist who has campaigned relentlessly against exploitation and oppression of adivasis of Bastar for more than three decades. It was his stint as Commissioner Schedule Caste and Schedule Tribes which helped raise many issues of concern. His opponents representing corporate interests were so incensed by his opposition to various alleged development projects and his raising uncomfortable questions about employment etc resulted in his humiliation when he was stripped nearly naked and paraded in Jagdalpur town. He took premature retirement from IAS and became a social activist in service of people.

(4) Home Minister P Chidambaram of the “dream team” fame had famously said on April 17, 2009 that “development can take place only when police action has secured the area.(of Maoists)” Thus going by his argument this government has no intention to do anything before ridding an area of the Maoist “bandits” or “terrorists”. Of course, to be fair to him, neo-liberal imagination considers development as being coterminous with corporate development. In turn this requires land, any which way, privatization of river water whatever the consequence, forest alienation and all this unmindful of loss of livelihood and environmental degradation. So the future that awaits us Indians after we are rid of ‘bandits/terrorists’ is capitalist profiteering. Is it any wonder that many regard state as the terrorist par excellence?

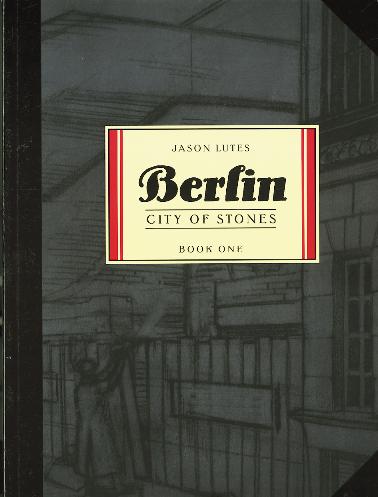

to the audio-visual experience of cinema than the culture of print to which comics have traditionally belonged. For him, not unlike the other contemporary graphic-novel greats such as Art Spiegelman, Alan Moore and Joe Sacco, words and images are not, as they traditionally have been in comics, discrete entities illustrating each other. Rather, they are envisaged as a singular, mutually illuminating complex whose dynamic makes possible ideas and occurrences that become the constituent units of the larger narrative. And Berlin is a perfect exemplar of Lutes’ vision steeped, self-admittedly, in the politics and aesthetics of avant-garde European cinema that has been summed up rather well by Jean-Luc Godard when he distinguished such cinema as a means of expression from television as a means of transmission.

to the audio-visual experience of cinema than the culture of print to which comics have traditionally belonged. For him, not unlike the other contemporary graphic-novel greats such as Art Spiegelman, Alan Moore and Joe Sacco, words and images are not, as they traditionally have been in comics, discrete entities illustrating each other. Rather, they are envisaged as a singular, mutually illuminating complex whose dynamic makes possible ideas and occurrences that become the constituent units of the larger narrative. And Berlin is a perfect exemplar of Lutes’ vision steeped, self-admittedly, in the politics and aesthetics of avant-garde European cinema that has been summed up rather well by Jean-Luc Godard when he distinguished such cinema as a means of expression from television as a means of transmission. Such filmic techniques also come in handy for Lutes to underscore the often contingent nature of decisions that people made while choosing their political side. For instance, the seeds of worker Gudrun Braun’s induction into the KPD (Communist Party of Germany) and her eventual death in the May Day massacre is sown in a serendipitous encounter between her and David, a young Jewish boy, whom she chances upon selling the KPD paper in heavy rain and who gives her a copy of the paper in return for the good turn she does him by lending him her umbrella.

Such filmic techniques also come in handy for Lutes to underscore the often contingent nature of decisions that people made while choosing their political side. For instance, the seeds of worker Gudrun Braun’s induction into the KPD (Communist Party of Germany) and her eventual death in the May Day massacre is sown in a serendipitous encounter between her and David, a young Jewish boy, whom she chances upon selling the KPD paper in heavy rain and who gives her a copy of the paper in return for the good turn she does him by lending him her umbrella.

A Review of “Global Neoliberalism and Education and its Consequences”

Madhu Prasad

Dave Hill and Ravi Kumar (ed), Global Neoliberalism and Education and its Consequences, Routledge, 2008.

This is an important collection of articles which focuses on theoretical issues and policy analyses to bring life and meaning to the facts of the crises facing educational institutions the world over.

Neo-liberalism has resulted in the merchandization of knowledge under conditions that subject its content, structures and modes of accessibilty to the pressures of a global market. The impact on the entire gamut of educational policy and practice has been devastating. As Nick Grant states in the ‘Foreword’ (xv-xvi), the “essentially social and cooperative ethic derived from a natural model of child development, which has informed most educationalists in most countries for centuries, is now challenged by a highly personalized and competitive model of education derived from modern business methodology.” Ravi Kumar and Dave Hill’s ‘Introduction’ outlines the significant social repercussions of this shift from pedagogical to market values. In conditions of increasing socio-economic disparities and loss of opportunities for the disadvantaged sections of society, the state is rapidly retreating from its earlier role as provider and guarantor of ‘welfare’ services, including education, that had ensured the ‘massification’ of skills required by the productive capitalism of the 20th century until the ’70’s. Cuts in public expenditure have since facilitated dependence on markets and opened up avenues for privatization of the education system. As a consequence, fundamental concepts like equality have been called into question. This remains an abiding concern throughout the many contributions to the volume.

Hill and Kumar (‘Neoliberalism and its Impact’) further demonstrate through an account of the British experience of systemic degeneration induced by neo-liberal pressures, how the ‘philosophical incompatibility’ between the demands of capital and the demands of education is increasingly being resolved by governments on terms that are more and more favourable to capital. In an ideological and economic reproduction of the dominant Thatcherite conception of social development, critical thought has been replaced by an instrumentalist rationality driven by market values. The loss of academic autonomy has led to an undermining of the role and status of the educator, a feature that is becoming characteristic across societies as the World Bank-IMF inspired structural reforms, pressing for withdrawal of the state from education and other services, are imposed on developing countries.

governments on terms that are more and more favourable to capital. In an ideological and economic reproduction of the dominant Thatcherite conception of social development, critical thought has been replaced by an instrumentalist rationality driven by market values. The loss of academic autonomy has led to an undermining of the role and status of the educator, a feature that is becoming characteristic across societies as the World Bank-IMF inspired structural reforms, pressing for withdrawal of the state from education and other services, are imposed on developing countries.

Henry Giroux (‘Neoliberalism, Youth and the Leasing of Higher Education’) identifies the youth as the worst sufferers of this “market ideology… reaching into and commodifying all aspects of social and cultural life.” (p 30). With the state no longer assuming responsibility for a range of ‘social needs’, agencies of government are carrying out policies of deregulation and privatization that are undermining the once “non-commodified public spheres that serve as the repository for critical education, language and public intervention” where democratic values and social relations “are learned and take root”. (p31). Giroux forcefully argues that the “death of the social, the devaluing of political agency, the waning of noncommercial values, and the disappearance of noncommercialised public spaces have to be understood as part of a much broader attack on public entitlements….” (p 46). All social safety nets having collapsed, a neoliberal Hobbesian ethic prevails in which all public concerns are “understood and experienced as utterly private miseries… (and) the losers vastly outnumber the winners.” (p 32) Since neoliberalism sees youth as a commodity, and young people only as consumers – otherwise they are a ‘social problem’ controllable only by a “rhetoric of fear, control and surveillance” – today’s youngsters represent the broken promise of capitalism in the age of outsourcing, contract work, deindustrialization and deregulation.

The market has no way of dealing with social inequality or civil rights. It has no vocabulary for addressing respect, compassion, ethics, or what it means to recognize antidemocratic forms of power. Giroux advocates struggle for a re-assertion of higher education as a public or social good, for democratic principles of inclusiveness and non-repression provide citizens with the critical tools necessary for investing public life with vibrancy and expanding the base of freedom and justice. As such, faculty resistance against corporatisation would certainly mean struggles for job security and academic freedom, but it must also mean the dynamic of “engaged academics” and “public intellectuals” interacting with student protests for peace, greater freedoms and against exploitation and oppression.

The ‘democratic deficit’ of neoliberal institutions like the WTO and trade regimes like the GATS, is also focused by Pierrick Devidal (‘Trading Away Human Rights?’). The global regulatory systems of neoliberalism are marked by the conception of a right to education as a utility, whereas the socialist-democratic perspective projects education as a non-utilitarian empowering right. “The normative arguments advanced for the protection of human rights are deontological: they focus on principles about how people are to be treated, regardless of the consequences”. (F.J. Garcia, Protecting the human rights principle in a globalizing economy,2001. Quoted p 92).

Hill, Greaves and Maisuria (‘Education, Inequality and Neo-liberal Capitalism: A Classical Marxist Analysis’) provide an account of the class systemic nature of the increasing inequalities resulting from neoliberal economic conditions and educational strategies. They point to the inherent tendency within the system to segregate the privileged in ‘good’ institutions, while relegating the poor, minorities and other disadvantaged sections to sub-standard multi-track schools without adequate resources or infrastructure. Markets only serve to exacerbate existing inequalities: “the poor have less access to pre-school, secondary and tertiary education; they also attend schools of lower quality where they are socially segregated. Poor parents have fewer resources to support the education of their children, and they have less financial, cultural and social capital to transmit.” (F. Reimers, Unequal schools, unequal chances. The challenges to equal opportunity in the America, 2000. Quoted p 119). Only policies that explicitly address inequality, with a major redistributive purpose, could make education an equalizing force in social opportunity.

Tristan McCowan’s critique (‘Higher Education and the Profit Incentive’) of J. Tooley’s neo-liberal opposition to state intervention in education identifies and elaborates “seven virtues of the profit motive” at the core of Tooley’s approach. Therefore McCowan sees his own argument as a “moral and not simply a pragmatic one… for the ability of states to defend their public education system, and for the notions of equality of opportunity and democratic control on which the systems in principle rest.” (p 55).

The claim that under neoliberalism successful modern economies “will be those that produce the most information and knowledge – and make that information and knowledge easily accessible to the greatest number of individuals and enterprises”, is examined by Nico Hirtt (‘Markets and Education in the Era of Globalized Capitalism’). Is it higher education, he asks, or the scarcity of it, the competition for it, that makes it so profitable for individuals and firms? Isn’t a flourishing economy the condition for boosting higher education and drawing investment into the area? ‘Unleashing the potential’ of those who have been unjustly left behind in a stratified, unequal society does require providing them with the weapon of knowledge and organizational capacity. But is this what our schools provide? And is this what we expect of them? Hirtt exposes the neoliberal claim of promoting a ‘knowledge-economy’. Given the volatility of the economic, industrial and technological environment, knowledge has become “a perishable product”; the important activity in education is not learning but “learning to learn”, that is, the acquisition of an ensemble of knowledge skills that are less institutional and more informal. Such “modular qualifications” (know-how, personal behaviour and development) are essential to be able to adapt to the evolution of, and the upheavals in, the job market.

Edwardo Domenech and Carlos Mora-Ninci (‘World Bank Discourse and Policy on Education and Cultural Diversity for Latin America’) provide a historically contextualized view of World Bank functioning. Co-opting a range of governmental and nongovernmental organisations, it ensures that their functioning remains complementary to the market, acting to make its functioning better and correcting its flaws. Together with international agencies and national governments, the Bank “seeks to gather together public officials, academics, designers and beneficiaries of nongovernmental programs, with the aim of revising its strategies and policies in search of new agreements and political support for its economic and social reforms. In this process, the WB procures the involvement of all public, private and nongovernmental agencies that are seen as complimentary to the optimization of the programs to reduce government expenditures. It is also important to note that the relationship between the WB and these international, governmental and nongovernmental organizations is not linear or unilateral… The WB was compelled to modify its discourse during the 1990’s due to heavy criticism and opposition from various social and political entities, especially the so-called new social movements.” Consequently, the “Bank’s discourse has become an odd mixture of decontextualisation, generalization, distortion and omission… as if the WB itself were not one of the key international actors that has engineered the so-called new international order.” (p 156-7).

Propagating the theory of human capital and education as investment, WB relies on an individualist perspective that promotes personal challenge over structural conditions of inequality, making each individual solely responsible for their own successes or failures. However, neoliberal individualism differs from classical liberalism in that it has lost the social component. Compensatory and targeted policies substitute the idea of equality for that of equity, the notion of common interest for particular interest, an ethics of personal gain that sees itself as being in contradiction with, and threatened by, the search for the well-being of society.

Such policies of assistentialism consolidate the segregation and fragmentation of education circuits, neutralizing the pedagogical function rather than complementing it. For example, the marginalization, asdisadvantaged groups, of indigenous communities and diverse minority groups, results in strategies for maximizing enrolment and ensuring retention, but fails to question the ability of the system itself to prove adequate to the pedagogical value and challenge of pluralism. This results in the “deterioration of pedagogical practice at the level of elaboration of pertinent strategies, as well as at the level of representations and expectations that allows generating actual learning in children”. (p 158) A pedagogy centred on the political critique of identity and difference, exposes the assimilative attempt as reinforcing the actual structures of power and domination by its understanding of socio-cultural diversities as the nonconflictual or unhierarchical coexistence of different communities/ groups. Societies are not homogenous and the specific power structures within their great social variety require to be uncovered.

The final contribution of the volume, Curry Malott’s ‘Education in Cuba: socialism and the encroachment of capitalism’, looks at the Cuban experience to see what can be learned about resisting the contemporary phase of capitalism. Cuba allocates over 10 percent of GDP to education, has one of the finest life-long teacher training programmes in the world, and has achieved universal school enrollment and attendance. Despite the hardship imposed by the collapse of the Soviet Union and the continuing illegal US economic embargo, the quality education the system provides to all “makes it first amongst all countries in the world… (and) we are sharing this immense human capital with our sister nations of the Third World without charging a cent.” (Fidel Castro, 2002). This ‘globalization’ stands out in stark contrast to neoliberalism, but is also subjected to global market pressures. Cuban state capitalism, the basis of its great provider role which still has the support of the majority of the population, is being forced to reprivatise and open sections of its economy to foreign investment to provide employment for the “best-educated and healthiest population in Latin America”. Education is the site of an inherent tension between learning as empowerment, the great egalitarian leveler, and learning as the social reproduction of labor power. While Cuba remains an inspiration as to the magnitude of human progress that can be achieved by resisting neoliberalism, it also serves to emphasize the fundamentally dehumanizing nature of value production under capitalism.

This is also the message and the understanding conveyed by the volume as a whole. Covering a wide range of concerns about the process of education, perhaps the most significant social activity apart from production itself, it is obvious that many issues taken up in this collection are debatable, that statements and arguments can be controversial or better framed, that many theoretical concepts and positions could have been included or explored in greater depth. However, given the stimulating achievements of the volume, these questions are best left to continuing debate and discussion.

Madhu Prasad teaches in the Department of Philosophy, Zakir Husain College, University of Delhi.