Satyabrata

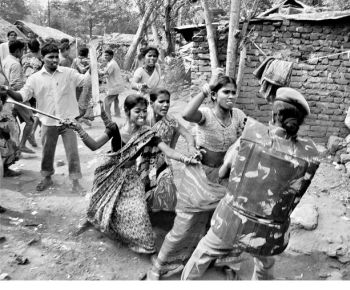

Two hundred and fifty-nine families (1195 people) resided in sixty year old Narayani Basti (slum near Unit 8 DAV School, Bhubaneswar) till the 29th of January 2011. On the 29th of January 2011, ten platoons of police with 9 platoons armed force and DCP and Commissioner of police went into the region and demolished the slums. Slum dwellers protested and many of them were seriously injured in their struggle against local goons and police who assaulted women. The police arrested hundred slum dwellers which included forty nine women. These women were kept locked in a van and were not allowed to leave the van for any reason. On the 30th of January local goons present did not allow either food or water to reach these people after they forcefully returned to their slums. Food prepared by the people from outside (Basti Suraksha Manch) was also not allowed to reach these people. The people organized themselves and started throwing stones at the local goons to get some time to collect and store food. Dodgers came again but this time failed to oust the organized masses. The people of the slums have now decided to take up arms (anything they have at their disposal, hammers, knives, etc) against anyone who tries to come to attack them.

Courtesy: The Hindu

These people living in the slums of Narayan Basti have been attacked by the police without Notice several times before. For the first time it happened in 16th of December, 2009 and since then there has been continuous opposition by slum dwellers against any attack by the forces of the Government. Through protests, they have been able to force dodgers back that had come to demolish the slums and this they have been able to do for about seven to eight times. The recent attacks before the demolition were made continuously from the 10th to 14th January, 2011.

There are several such slums in Bhubaneswar who fear demolition and the Basti Suraksha Manch of Bhubaneswar is playing a leading role in organizing these people. According to the Basti Suraksha Manch, the demolition of these slums is illegal. According to Orissa Municipal Corporation Act Chapter 21, slums are classified as Tenable (which can’t be moved to other places) and Untenable (which can be moved to other places). The Narayan Basti slum is declared Tenable according to this act with its code being 3301 (every slum has a code). In spite of their having tenable status, the Government doesn’t even give alternative accommodation, rather, has a ‘transit house’ (about three kilometers away in Niladri Vihar) where these people will be given accommodation for 15-30 days only and will be left to their own. One can judge how the Government sees its people when one finds that these transit houses have two toilets for two hundred families.

The following is a copy of the letter written to Chief Justice of Orissa High Court:

The Honourable Chief Justice

Odisha High Court, Cuttack

Sub: Pray for justiceSir,

49 women of Narayani Basti (Khandagiri PS, Bhubaneswar) are illegally detained in the Khandagiri PS at night(after sunset) on dtd.29.01.2011. Who were forcibly evicted from their slum in spite of High court judgment in writ petition(C) No. 11667/2010 and writ petition(C) No. 12723/2010.

You are therefore, requested to kindly intervene the matter in the interest of justice.

Yours faithfully,

Pramila Behera

Plot No. 1819 (opp N6/10)

IRC Village, Bhubaneswar-15

A Review of “Finding Delhi: Loss and Renewal in a Mega City”

Ankit Sharma

Bharati Chaturvedi (ed.) Finding Delhi: Loss and Renewal in a Mega City, Penguin Books India, New Delhi, 2010

Delhi is often thought of as the culturally best endowed city in the country. It has had a rich heritage, from the Walled City of the Mughals (presently called Old Delhi) to the Lutyens’ capital of the British raj; now there are chains of multinational corporations working in the peripheral areas of the city, and the city has declared its “world-classiness”, reshaping its infrastructure to host the grand spectacle that was the Commonwealth Games. Hence, most writings on the city stick to celebrating the warm-heartedness of the “dilliwallas,” its ever increasing count of flyovers and shopping-malls. Weighed down by such images that flood the media Finding Delhi comes as a relief to its reader because it tries to engage with that part of Delhi that is left out in the sort of accounts mentioned above: the not too pretty underbelly of the Indian capital. The book offers an account of the city culled out of the experiences of fourteen different writers, ranging from urban planners to informal-sector workers, concentrating on diverse urgent issues like public transport, women in the city, housing rights of the poor, problems faced by street vendors, and the situation of the homeless ahead of the Commonwealth Games. The writers try to represent the city from an unconventional angle, where they concentrate on the living conditions of the poor living in the city, and the damage done to their lives due to the infrastructural developments that have taken Delhi way “ahead” of cities like Mumbai and Kolkata. It can, in fact, be argued that the book aims to confront the middle class, whose India is “shining”, with this “other angle” in an attempt to make them to realize that the actual cost of this accelerated drive toward “development” is being paid by the poor, in the form of ever deteriorating living conditions; presumably the monologues of a waste collector, a domestic worker, a dhobi and a fruit vendor are included in book to fulfill this end.

The book is divided into three parts: “Cityscape”, “Challenges” and “Experiences”. The first part explores how lines of class and gender demarcate the urban space. It begins with an article by Amita Baviskar that looks into how the newly reconfigured urban space of Delhi excludes the poor. She takes the example of the Vishwavidyalaya metro station, where an adjacent plot of land was allegedly allotted for a mall, when it could have been used as a park, or to house the poor. She elaborates her point by citing the example of the jhuggi-jhopdis near Majnu Ka Tila that were demolished in order to provide land for a private apartment builder. Our own experiences over the last few years offer us enough examples to buttress this point; for instance one can look at the manner in which the poor were not only neglected, but even hidden behind hoardings and posters during the CWG fiasco. This article is followed by a historical/analytical essay on Delhi from pre-colonial to post-liberalization times by Lalit Batra. Batra explores the history of the Delhi poor, and argues that the exclusion that, for instance, Baviskar speaks about is nothing new, and is an integral part of how the administration functions. For the state, land is capital, to be used optimally, and slums do not allow this optimum use, as a High Court ruling on land squatting proves.

space. It begins with an article by Amita Baviskar that looks into how the newly reconfigured urban space of Delhi excludes the poor. She takes the example of the Vishwavidyalaya metro station, where an adjacent plot of land was allegedly allotted for a mall, when it could have been used as a park, or to house the poor. She elaborates her point by citing the example of the jhuggi-jhopdis near Majnu Ka Tila that were demolished in order to provide land for a private apartment builder. Our own experiences over the last few years offer us enough examples to buttress this point; for instance one can look at the manner in which the poor were not only neglected, but even hidden behind hoardings and posters during the CWG fiasco. This article is followed by a historical/analytical essay on Delhi from pre-colonial to post-liberalization times by Lalit Batra. Batra explores the history of the Delhi poor, and argues that the exclusion that, for instance, Baviskar speaks about is nothing new, and is an integral part of how the administration functions. For the state, land is capital, to be used optimally, and slums do not allow this optimum use, as a High Court ruling on land squatting proves.

The next article also works along similar lines, arguing that the work that the poor do is absolutely essential to the city’s functioning, though the rich do not acknowledge this. It describes the workers who work in scrap-yards where old, now-useless items are recycled; now with the government giving out tenders to private companies, to dispose of this scrap, the employment of these people is in danger.

The critique that these articles offer touch our “humane side” and force us to acknowledge that the poor are indeed hard done, and that something must be done for them, so as to ensure in Delhi, a perfect balance between “classiness” and humanity (presumably evidenced by improved life conditions of the poor); this is of course the balance wished for by all these writers. Herein, strangely, lies the problem with these critiques. The majority of these writers seem to call out to the middle-class to go beyond their “petty needs”, to feel for the condition of the poor and also that it is up to them to do “something” about it. They do not seem to understand that this compassion is itself premised upon the existence of these conditions. Capitalism creates inequality so that a small number of people can exploit and extract surplus value from a much larger number of poor people. The city, the ultimate symbol of modernity and of capitalism, is also the ultimate breeding ground for these social-relations. The editor of the present book claims that the main aim of the book is to provide a critique of the present developmental model adopted by the government; evidently the book offers not post-facto theorizations, but seeks to serve as a manifesto for concrete actions to be taken in the future, for the city’s benefit. Hence, the book has a special section called “Challenges”, in which authors highlight the issues which need to be addressed immediately. Sadly, though not surprisingly, this section of the book, that comes after the initial discussions of the pro-rich shaping of the city, moves straight to issues like cleaning of the Yamuna, and to the experience of a writer who spent an entire night roaming the streets of Delhi, looking after homeless people etc; despite the implicit insights provided by the earlier essays no mention is made of how capitalism and its state are responsible for these problems. Coming to think of it, even the earlier essays pose this question as one of reform; the incessant struggle between labor and capital that is reflected in the cityscape was un-mentioned and in essence it was argued that all problems could be solved if only the government were to look after the poor a little better. One writer, anxiously, even speaks of the possibility of the poor taking over Connaught Place, the India gate, and Gurgaon – what would happen then? The possibility of a revolution and a post-revolutionary state clearly make this writer uneasy. She is unable to appreciate the idea of a laborer controlling her/his labor – something which is common enough in NGO-type activism.

At present, in India, large companies (Tatas, Birlas, Ambanis etc) are monopolizing all industries, and are now making a move even into the informal sector. It’s common to come across supermarkets like Big Bazaar, Reliance Fresh, Big Apple etc, and clearly local fruit and vegetable sellers are unable to compete with them. The case of the waste-pickers is evidence of the same state affairs. However the book does not take the reader beyond this level of appearances; which is to say that it does not go into causes. The causes that underlie this state of affairs are too deep, too endemic to this system to be solved by human goodwill (the leitmotif of NGO-activism).

A couple of other articles, however, do seem to try go beyond the surface, and in that seem to be able to keep off turning these issues into questions of ethics and morality. For instance in an article titled “Delhi: Expanding Roads and Shrinking Democracy”, Rajinder Ravi tries to bring across to the reader the plight of workers who used to cycle everyday to their respective workplaces (anyone who travels from East to Central Delhi will be familiar with the sight of thousands of workers cycling to work through cycle-lanes). The changes that were brought in preparation of the Commonwealth Games destroyed the cycle lanes to expand roads. While to the “average” Delhiite (actually only the middle/upper class) the expansion of roads has come as a boon because they use cars and motorbikes to commute, for the lower class it has meant a move to the more expensive public transports of the city (not to mention the environmental cost involved in the move made from cycles to buses etc).

Similarly in “New Delhi Times: Creating a Myth for a City”, Somnath Batabyal, a former journalist takes on the ever so active torchbearer of our society – the “Media”. The writer presents to us quite an interesting take on the media and the type of work that they do. He shares with us two instances where media houses were campaigning actively, and were believed to be the face of the aam-janata, the “Campaign for Clean Air” in the 90’s and the recent anti-BRT campaign. The writer speaks of how media personalities work according to the interests of the middle class, for a city in which the poor have little for them. The media that had once campaigned for a clean, pollution free environment turns coat the moment this idea of a “clean environment” comes into conflict with the “shining India” of the middle class, and jumps into a drive against the BRT, a project which, if properly managed could help control pollution by limiting the use of private transportation. As is rightly pointed, a majority of the bourgeois environmentalists and journalists live around the corridor and use it to commute to their offices everyday. Due to the construction of separate lanes for buses and cars, these drivers have a hard time on the road; this did not go down well with these media persons and hence the anti-BRT media campaign.

The article mentioned above does try to look at least this one problem through the optics of class struggle; but because of the book’s attempt to present a “kaleidoscopic” view of perspectives coming from different ideological tendencies, its emphasis on solving the problems of the poor gets lost. Even the monologues from the informal sector workers get mixed up in this cacophony of perspectives and do not serve any purpose except giving an appearance of the editor’s “democratic” designs. Failing to connect apparent problems to the fundamental underpinnings of the system, such attempts fail to see how perspectives on these problems are also in some sense takes on the system. It is not enough to allow everybody to speak, since the interests of some, a priori are against the interests of the poor that they nonetheless may seem to defend. In the final analysis the sort of reformism that this attempt represents acts as a pressure release valve, to negate the possibility of genuinely transformative collective action. The book fails to rise above the philanthropy that is also called “social activism”, and in that fails to reach toward a useful plan of action. But to its credit, it does succeed in throwing a somewhat different light on the state of Delhi, in a situation where the state and its media are feeding us on a diet of neoliberal propaganda; for those used only to the “mainstream” it could offer a useful change.