Michael Perelman

Louw, P. Eric. 2010. Roots of the Pax Americana: Decolonization, Development, Democratization and Trade (Manchester: Manchester University Press).

The United States, like Germany, came late to the empire business. It did not aspire to informal Empire, but rather went to great lengths to undermine the existing empires to open them up for US business. Eric Louw tells the story very well.

In his account, the US was going to great lengths to undermine Britain’s Empire, especially India, even when those powers were allies during the Second World War. He attributes Chamberlain’s behavior in Munich to a justifiable fear that dependence on US support in fighting the Nazis posed a greater threat to the empire than the Nazis themselves. He shows that the US made good use of Gandhi in discrediting the British Empire.

Rather than going to the expense and trouble of maintaining a formal Empire, the US preferred finding compliant regimes in important venues. For example, the US could have kept Cuba as a colony, but it got what it needed much more cheaply by keeping friendly governments in place. In contrast, Puerto Rico, which was much smaller, would not pose much trouble as a territory controlled by the US.

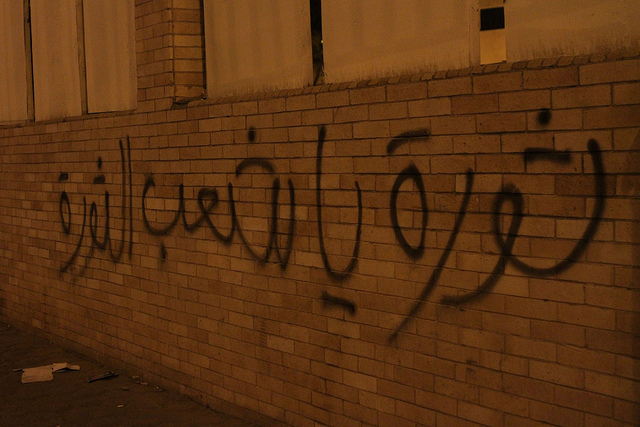

The book does not seem to be intended as a radical critique. It does not discuss how this Pax (Pox) Americana proved to be a disaster, leaving people under the rule of Marcos, Mubarak, the Shah, and other such klepocrats and thugs I am anxiously waiting new chapter being written today in the streets of the Middle East.

‘It prefigures for the Arab people a new horizon’: Vijay Prashad on the Arab revolt (Part II)

This is the concluding part of our interview with Vijay Prashad, a prominent Marxist scholar who teaches at Trinity College, Connecticut. To read the first part, please click here. His recent book, The Darker Nations, was chosen as the Best Nonfiction book by the Asian American Writers’ Workshop in 2008 and it won the Muzaffar Ahmed Book Award in 2009.

Pothik Ghosh (PG): Why is it that most attempts in the Perso-Arabic world to conceptualise what Gramsci called the “national-popular” have come from radical left-nationalist intellectuals such as Edward Said rather than Marxists? How should or could the peculiarity of the Saidian theoretical enterprise of the national-popular inform and enrich working-class practice in West Asia?

Vijay Prashad (VP): Strictly speaking, Gramsci’s “national-popular” is the emergence of the mass throughurban collective action, with the rural bursting through, and then being guided by the Jacobin (his word for an organised political force). The mass might drift into a-political action or passivity, Gramsci wrote, without the guidance of that Jacobin force. In today’s times, there is a tendency to hear about something like the Jacobin and shiver in fear that the energy of the “multitude” will be usurped by the Jacobin, that the authentic politics of the street will be taken over by the Organisation. It is in essence a misreading of anarchistic politics that this sort of fear has taken hold. I do not believe that anarchism is pure disorder; for those who believe this I propose a reading of Errico Malatesta’s “Anarchy and Organisation.” Of course, for those on the Marxist side of the ledger, Gramsci’s comments are our bread and butter. There is a need for the national-popular to be articulated through mass protest and the Jacobin canals. There is not so much that divides the Black and the Red.

It is not the case that only Edward Said has dealt with the national-popular in the Arab world. Take the case of Lebanon, where it is the Marxist historian (and eminent journalist) Fawaz Trabulsi who has written a remarkably informative account of the thwarted national-popular, with the emergence of Hezbollah. To my mind, Trabulsi’s is the best account of the Lebanese problem. It must be read widely to better understand the national dilemmas and the national-popular potentialities. My own interest in the Arab predicament was partly drawn by the work of people from an earlier generation like the writer and PFLP leader Ghassan Kanafani, who was assassinated in 1972. In the context of this new Arab Revolt, I recommend Kanafani’s pamphlet The 1936-37 Revolt in Palestine, a model for how to theorise the national-popular through the material of a revolt. These are role models for those who want to do detailed work on the Arab potential. The contingent is important, no doubt, but so too are the broad structures that need to be unearthed and developed.

PG: Lebanese-French Marxist Gilbert Achcar writes in his ‘Eleven Theses on the Current Resurgence of Islamic Fundamentalism’: “What is an elementary democratic task elsewhere – separation of religion and state – is so radical in Muslim countries, especially the Middle East, that even the “dictatorship of the proletariat” will find it a difficult task to complete. It is beyond the scope of other classes.” Does the ‘Jasmine’ Revolution portend a change for the better on that score? If not, how, in your view, should the working class forces in the region go about their business of shaping an effective ideological idiom that is rooted in local culture and yet articulates a question that is fundamentally global?

VP: We tend to exaggerate the authority of the clerics, or at least to treat it as natural, as eternal. Certainly, since the 1970s, clericalism has had the upper hand in the domain of the national-popular. In the Arab world, this has everything to do with the calcification of the secular regimes of the 1950s (the new states formed out of the export of Nasserism: from Egypt to Iraq), the deterioration of the Third World Project (especially the fractures in OPEC that opened up in the summer of 1990 and led to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait), and the promotion and funding of the advance guard of the Islamism through the World Muslim League (by the Saudis. The WML’s impact can be seen from Chechnya to Pakistan, and in parts of Indonesia).

If one goes back and looks at the period when the Third World Project and Nasserism were dominant, what you’d find is clerical intellectuals in the midst of an ideological battle against Marxism (mainly), at the same time as they borrowed from Bolshevik techniques of party building to amass their own organisational strength. I wrote about this in New Left Review (“Sadrist Stratagems,” in 2008) where I catalogued the intellectual work of Baqir al-Sadr, with his Iqtisaduna, a critique of Capital Vol. 1. Baqir’s al Da’wah al-Islamiyah was modeled on the Iraqi Communist Party, then dominant in the Shia slums of Baghdad. If you go farther East along this tendency, you will run into Haji Misbach, an Indonesian cleric, also known as Red Haji, who confronted the dynamic Indonesian Communist Party with his own brand of Islamic Communism. Like Baqir, Misbach was perplexed by the popularity of the CP in his society. He wanted to find a way to bring the spiritual to socialism. These are all precursors of Ali Shariati, the great Iranian thinker who was influenced by the Third World Project, and by Marxism, but once more wanted to bring the spiritual into it. For all these thinkers, the problem was quite the opposite to what it is today: the workers seemed ascendant, driven by the science of secular socialism. It terrified them, as much as we are assaulted by the rise of the clerics over the last few decades.

It is also not the case that the religious is more difficult to expunge in the Arab lands, or that Islam is more intractable than other faiths. If one turns toward India, or turns toward the United States, it is clear that the religious domain is often very reluctant to wither away. It was equally hard to push it away in the USSR. This is not just a question of religion, or Islam, but of cultural change in general. Cultural change from below is slow-moving, excruciating. Cultural change from above is much faster, the tempo clearer. It has to do with who controls the cultural institutions, but also with the depth of cultural resources. Religion emerges over the millenia as a shelter from the turmoil of life, and it enters so deeply into the social life of people that it cannot be so easy to remove its tentacles. Of course Islam might be harder to walk away from, given that it, unlike say Brahmanism or Catholicism, has a much finer edge to its egalitarianism. This is what propelled it from a minor Arabian religion to Andalucia and China within fifty years of its emergence.

I would say one more thing on this: since the Utopian horizon of socialism is in eclipse, why should someone risk their lives in struggle for it? The idea of the inevitability of socialism inspired generations to give themselves over to the creation of the Jacobin force. Religion has an unshakable eschatology, which secular politics absent Utopia lacks. No wonder that religion has inspired action, even if destructive rather than revolutionary, whereas secular politics is less inspirational these days.

The Arab Revolt of 2011 prefigures for the Arab people a new horizon. That is why it has moved from Tunisia to Jordan. Ben Ali’s departure set the new horizon. It is what the youth hold onto. If he can be made to flee, why not Mubarak, why not Abdullah II, and if the remanants of the Saudi Voice of the Vanguard decide to blow off the cobwebs and get to the streets, then the repellent Abdullah of Saudi (whose idea of political reform was to bring in his son-in-law into the Education ministry!).

PG: Does not the ongoing ‘Jasmine’ Revolution explode the myth of a postcolonial, anti-imperialist Third World, which is precisely what you deal with and kind of theoretically anticipate in your book The Darker Nations? If that is so, what is the new programmatic direction that the anti-imperialist struggle must now take?

VP: My book, The Darker Nations, provided the history of the collapse of the Third World Project. This collapse begins to be visible by the early 1980s. The roots are there in the defeat of the New International Economic Order (NIEO) process (that opens in the UN in 1973), in the break-down of solidarity in OPEC, in the exhaustion of the import-substitution industrialisation model, and in the narrowing of political freedoms in the Global South. The “assassination” of the Project comes through the debt crisis (1982 in Mexico opens the door) and through the reconfiguration of the international order by the late 1980s with the disapperance of the USSR, and the push for primacy by the US (the salvo was fired in Iraq in 1991, when the US pushed out the Iraqi army from Kuwait, and ignored an attempt by the USSR to mediate on behalf of Saddam Hussein). US primacy by the early 1990s throws salt on the wound of the Third World Project.

My interest in the book was to seek out the dialectics of freedom that would emerge out of the corpse of the Third World Project. What is left in it to be revived, and what are the social forces capable of building a new revolutionary horizon? The other side of history opens up with La Caracazo, the rebellion in Caracas in 1989 that prefigures the emergence of Chavez. By the way, in 2009, a Brookings survey found that Chavez was the most popular world leader in the Middle East! Where is Chavez of Arabia, we asked, but were not confident. In 2007, in his “Jottings on the Conjuncture,” Perry Anderson bemoaned the paralysis on the Arab Street. The mutterings existed, and indeed the insurgency in Iraq showed that the will was there. Protests in Western Sahara and in Lebanon had become commonplace. But these did not say what the Tunisians said, which was that they, like the Bolivarians, were prepared to stake themselves for an alternative pathway into the future. From Caracas to Cairo, the expressway of Freedom is being paved.

The Bolivarians are at a much more advanced stage. They have been able to stave off counter-revolution, and even though still in peril, they are able to leverage their oil wealth into some very interesting experiments toward socialism. It is going to be imperative to prove for our Egyptian and Arab friends that the path out of Ben Ali and Mubarak does not lead to Paris and New York, but to Caracas and La Paz. The programme of socialist construction is being tentatively written (with lots of errors, of course). We have to nudge in that direction, and against the idea of liberty as the value above egalitarianism and socialism. There are few explicitly anti-imperialist slogans in the air at this time.

By the way, this other side of history will form the final chapter of The Poorer Nations, which I am now putting together, and which should be done by the Summer of 2011.

PG: The ‘Muslim Question’ has rightly been one of the key preoccupations of the Indian Left in all its variegated multiplicity. Yet it has consistently failed to frame and articulate it as a question having a transformative potential. What lessons must the Indian Left – which has in large measure centred its articulation of the ‘Muslim Question’ on solidarity with the Islamicised anti-Americanism of the Perso-Arabic peoples – draw from the current upsurges that would enable it to overcome its failing on that score?

VP: To get to the heart of the issue of the ‘Muslim Question,’ one has to understand the theory of alliance formation. In today’s world, the principal contradiction, the Large Contradiction, is between Imperialism and Humanity. The social force of imperialism seeks to thwart the humanity of the planet by creating political rules for economic theft (the preservation of intellectual property for the Multi-national corporations, the allowance of subsidies in the North and not in the South, the enforcement of debt contracts for the South, but not for the international banks), and if these rules are broken, by military power. Imperialism is the principal problem in our planet, for our humanity.

The Lesser Contradiction is between the Left and the Reactionaries, who are not identical to imperialism. Indian Hindutva, American Evangelicalism and Zionism are all reactionary, but not part of the Lesser Contradiction. Those forms of Reaction are ensconced in the Larger Contradiction, since they are handmaidens of imperialism. What I refer to as the Reactionaries of the Lesser Contradiction are organisations such as Hezbollah and Hamas, the Muslim Brotherhood and so on. I indicate the Muslim groups not from an anti-Islamic point of view, but because, as I just mentioned, most of the other Reactionary religious formations are inside the essence of imperialism (they are joined there by the official clerics of Saudi Arabia, and of Egypt). These other groups are antagonistic to imperialism, and are from this standpoint able to capture the sentiments and politics of the people who are anti-imperialist nationalists. We are divided from them, but not against them in the same way as we are against Imperialism. To make these two contradictions the same is to fall into the liberal error of equivalence. We need to retain their separation.

That said, it is important to always offer a scrupulous and forthright critique of their shortcomings and their social degeneration. In 2007, the Communist Parties in India held an anti-imperialist meeting in Delhi. A Hezbollah representative (I think it was Ali Fayyad) came for it. At the plenary, Aijaz Ahmad lit into Fayyad regarding Hezbollah’s position on women’s rights. It is just what should be done. By all means form tactical alliances, if need be, but don’t let them get away with silence on the issues that matter to us, on social equality, on economic policy, on political rights. Even the Lesser Contradiction needs to be pushed and prodded. It has virulence at its finger tips. That has to be scorched. Clara Zetkin warned that the emergence of fascism can be laid partly on the failure of the workers and their Jacobin to move toward revolution effectively enough. Part of that effectiveness is to challenge those in the Lesser Contradiction, who are equally willing in certain circumstances to turn against the Left and become the footsoldiers of fascism.

In the 1980s, Hezbollah mercilessly killed cadre of the Lebanese Communist Party. Over the past three decades, relationships have mellowed and the much weaker LCP now works with Hezbollah in various ways. The LCP sees Hezbollah as “a party of resistance,” as it were. Part of the Lesser Contradiction. That has to be the attitude in the short-term. The LCP seeks out elements who are not fully given over to Dawa, the hardened Islamic militants in Hezbollah. There is another side that is more nationalist than Islamist. They are to be cultivated. There is also a part of Hezbollah that is perfectly comfortable with neo-liberalism, privatisation of the commons and so on. They too lean toward the Larger Contradiction. One has to be supple, forge a way ahead, be assertive in unity, find a way out of the weakness and reconstruct a left pole. A weak left with the national-popular in the hands of the “Islamist” parties: that is the context.